Online retailer Amazon is in the midst of building a sprawling campus in downtown Seattle that when completed will encompass five office towers and create some 4 million square feet of office space.

That’s a lot to heat during the Pacific Northwest’s winter months. So, it’s only fitting that, thanks to the work of Seattle-based mechanical contractor McKinstry Co., the digital juggernaut is warming the radiant floors at its new headquarters with heat "borrowed" from the very infrastructure that keeps Amazon itself, as well as the rest of the internet, the cloud and the tech universe, up and running every second of every day.

The Westin Building Exchange, one of the region’s most important internet hubs, is right across the street from Amazon’s Denny Triangle campus.

As a result of the McKinstry system, the Westin can curb the amount of waste heat generated by a skyscraper filled with servers, and Amazon will heat the three buildings that have already opened and provide warmth for the towers still to be constructed. In turn, the water from Amazon’s hydronic system is piped back to the data center to start the process all over again.

“For the Amazon buildings, the Westin building is functionally equivalent to 36 miles of drilled and filled ground-coupled hydronic loop,” says McKinstry engineer and preconstruction manager Adam Myers. “So, the mission-critical data center is a very powerful and reliable boiler. Meanwhile, to the Westin, the Amazon campus is functionally equivalent to a very large cooling tower.”

Westin Exchange

From the outside, the 34-story Westin looks just like any other downtown commercial office tower.

But inside runs a veritable river of copper wire and fiber cable powering floor after floor of server racks and other data center equipment, burning through 11 megawatts of electricity every day.

All that energy naturally ends up as heat with much of it simply wasted and vented through cooling towers atop the building and into the sky.

Just how much heat? Well-known Energy Vanguard blogger Allison Bailes noted that a typical server uses about 350 watts of electricity and produces about 1,200 BTUs/hr. of waste heat.

“With 50 servers, you could get as much heat as a 60,000 BTUs/hr. furnace,” Bailes wrote back in 2014 after Seattle city officials first approved the plan to use the waste heat from the Westin data centers.

As you may have guessed, the Westin used to be the headquarters for the Westin hotel chain when the tower opened in 1981. The hotelier moved out years ago around the time building management started profiting from deregulation transforming the telecommunications industry and began renting space to an entirely different type of tenant.

Since the 1990s, the building has served as a regional telecom “carrier hotel” that houses computer and server hardware for 250 telecommunications and internet companies. About 70 percent of the building is occupied by data centers throughout about 60,000 square feet of space.

In addition, the Westin is home to the Seattle Internet Exchange, the largest noncommercial member-governed internet exchange in the U.S. Participants peering on the exchange include no less than Amazon, but also Yahoo, Twitter, Microsoft, Netflix, Google and Facebook to name just some of the well-known digital brand names.

Added up, virtually all digital traffic in the Pacific Northwest goes through the Westin.

While there are examples around the world of other data centers and even old-school mechanical heating processes recycling waste heat, most of these cases use the heat “in house” for their own purposes.

The Amazon/Westin deal, however, is believed to be the first time that waste heat has crossed property lines.

How it works

As Myers suggests, it helps to think of the Westin as the “boiler” and the Amazon complex as a “cooling tower.” Between them is a loop and in the middle of the loop is the real magic: a waste heat exchanger designed and built by McKinstry.

The Westin uses a hydraulic system to cool the data center with water flowing through PVC pipe, naturally picking up heat along the way.

That water ultimately runs from the Westin through a 14-inch pipe under the city’s Sixth Avenue to the basement of the 37-story Doppler. The campus construction is a multiyear project with Doppler the first to be completed.

Also known as Amazon Tower 1, the building houses 3,800 employees. It takes its name from the codename for what eventually became the Echo, Amazon’s voice-controlled speaker.

The basement contains a 400,000-gallon reservoir tank that provides low-grade heat storage and an emergency water supply for Westin if needed. Meanwhile, a heat recovery chiller plant extracts heat that will be used for the Amazon buildings.

By the time the Westin water reaches the waste heat exchanger, the water is about 65 F, so it is run through a series of five heat-reclaiming chillers to raise the temperature to 130 F, thereby, also reducing the volume of water.

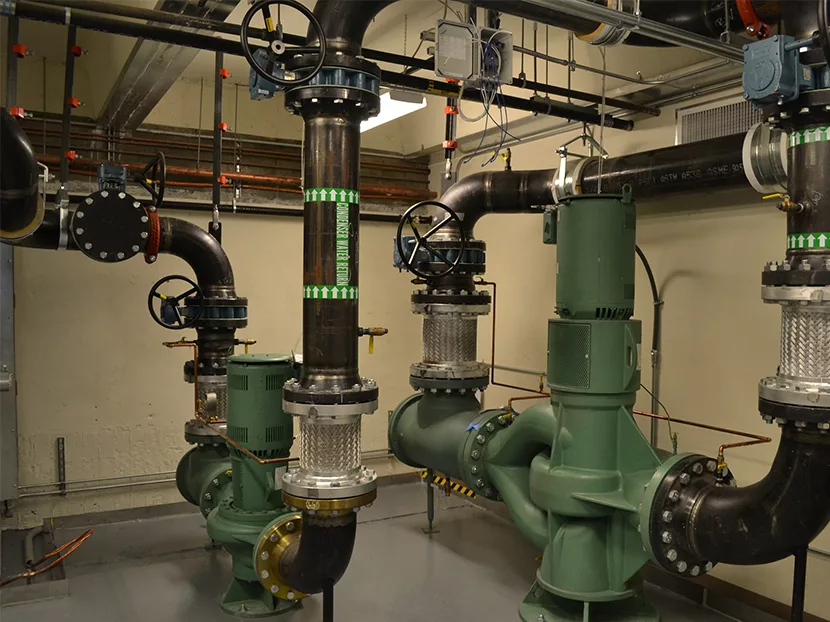

McKinstry used welded stainless plate for the high pressure multiple circuit heat exchanger, welded black steel 10- and 8-inch pipe inside the mechanical room, and PVC pipe underground between the buildings.

Contractors are used to installing their mechanical systems in tight spots. This job was no different. McKinstry built a 3D model to determine the appropriate piping “spool piece” size to carry into the building, fit down the elevator shaft, and meet elevator load restrictions.

Afterward, McKinstry prefabricated the project in its Seattle shop and delivered the 10,000-pound heat exchanger in five pieces, accompanied by custom-made carts.

Meanwhile, the cooled-down water from the hydronic system will then run back under Sixth Avenue in a parallel pipe to the data center where it will be used all over again.

“Not only are you saving fossil fuels that would be burned in the Amazon buildings to heat water, you're also saving on the electrical energy because the cooling towers are ramping down,” Myers adds. “So, it's really a win-win for both.”

What the Westin “boiler” lacks in power, it more than makes up for it in reliability. All that data center equipment must run 24/7, and the Westin has substantial backup generators standing ready to keep all those servers humming if the main utility's power source goes off.

As a Plan B, however, the system does include four boilers. But they aren’t called on much.

“They only turn on if there's a peak load,” Myers says, “where it's really, really cold outside.”

Amazon started moving into its new office space three winters ago. Since then, Myers says McKinstry analyzed the system’s performance details and made adjustments to “make sure we can further limit the amount of time the boiler come on.”

Collaboration

Data center heat recovery is an attractive option for data center owners of all sizes because it transforms the data center from an energy consumer into an energy producer.

The project as complicated as this required collaboration among Amazon, McKinstry, Clise Properties, which co-owns the Westin and also sold Amazon the land for its new headquarters, and city officials who cleared all the regulatory hurdles, such as allowing piping to transverse under public right of ways below city streets.

Myers says the planning began in 2012 with about a year and a half passing before the actual construction process began.

The heat-exchange infrastructure in the Westin building is actually owned jointly by McKinstry and Clise through a partnership called Eco District.

Eco District is a “micro-utility” designed to export up to 5 megawatts of waste heat from the Westin building to warm the Amazon campus, which Amazon purchases at a discounted rate.

Fully implemented, recycling waste heat will be four times more efficient than traditional heating systems, according to McKinstry, and save hundreds of thousands of dollars each year and about 80 million kWh of energy over the next 25 years.

In addition, the operator of the data center, Clise Properties, will save money on electricity and a lot of water.

The campus also benefits from having a system that can scale across multiple buildings, rather than one requiring individual units to be installed and maintained.

The Doppler building is expected to earn a federal ENERGY STAR rating of 98 out of 100 for its first year of operation.

“It’s working great,” Myers adds. “We hit exactly right on our targets for that first year of operation. And as the rest of the buildings are coming on, we're right in line to hit all our other targets.”