New Research Confirms What Most Thought Caused Flint Water Crisis

Research from the University of Michigan appears to confirm that improper corrosion control caused lead to leach into drinking water in Flint, Michigan.

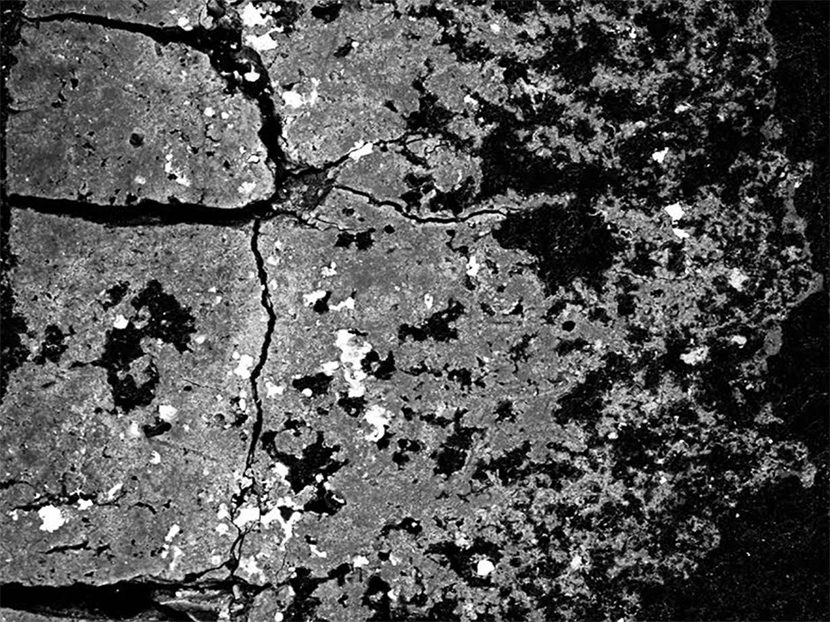

Using an electron microscope, the research team examined the layers of lead scale inside 10 service line samples taken from Flint homes as the city began replacing the lead lines. The greatly magnified images of the pipe revealed that the layer of rust that naturally develops around the inside of a water line developed a “Swiss cheese” pattern.

Afterward, the researchers pulverized the pipe samples to determine composition. What they found was a greater ratio of aluminum and magnesium to lead compared to the typical lead service line based on data from 26 other water utilities in the U.S. and Canada.

In other words, the corrosive water dissolved significant amounts of lead right off the pipe, and the holes in that Swiss cheese pattern were where the lead used to be.

Overall, the researchers contend that lead accounted for 30.7 percent of the weight in pipe residue before the switch to the Flint River. Using this estimate, they then approximated how much dissolved lead went into the water of individual homes during the disaster. They calculated 36 micrograms of lead per liter of water – more than twice the amount allowed by the EPA – flowed into homes over the course of the crisis.

At that rate, the lead concentration released over the entire period that the town used the Flint River for drinking water supply would have surpassed twice the EPA action level of 15 parts per billion.

While general public opinion and some previous studies blamed inadequate corrosion control for lead leaching into Flint’s water supply, the UM research is the first direct evidence.

Flint’s water troubles began in April 2014 when the city traded a corrosion-controlled water source from the Detroit Water and Sewage Department for the Flint River. Health concerns arose within months of the switch. Lead levels in one home’s tap water ballooned to nearly 50 times more than the EPA’s action standard.

Water utilities with both corrosive water and lead service lines in their systems add compounds called orthophosphates to prevent that breakdown. When Flint switched from Lake Huron, Detroit’s municipally treated source, to the more corrosive Flint River to save money, the utility didn’t adjust its treatment process by adding orthophosphates.

The researchers hope to verify their prediction of the amount of lead released by analyzing a lead service line from a vacant home that was not exposed to the corrosive Flint water. The challenge is to find a home that has had its water turned off since 2014 and has a lead service line that can be dug up.

A copy of the research can be found here.