America Goes Green

Congress has passed three historic bills since December 2020 that dramatically shift the country to clean buildings, energy and refrigeration.

As usual, in this column, I'm going to provide information about a couple of planet-friendly projects in the built environment: a new National Hockey League (NHL) arena and a small house with heat pumps.

We can expect that these will soon become business-as-usual in the United States. Congress has now passed three historic bills signaling that we are “all-in” with respect to cleaning up our planet. The Inflation Reduction Act, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act and the American Innovation and Manufacturing Act are dramatic confirmations of the country’s commitment to clean buildings, clean energy, clean transportation and clean refrigeration.

Inflation Reduction Act

Many who work in the built environment may ultimately be affected more by the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) than any legislation ever before passed in the nation’s capital. You have undoubtedly read about it; some programs are in a state of flux or still being interpreted by construction, media and environmental groups, and by states who will administer certain aspects of the legislation.

Some examples of probable outcomes relating to the construction industry include:

• Direct homeowner rebates. Until 2031, the government will provide $4.28 billion in rebates, up to a total of $14,000 per household. Direct rebates are for low- and moderate-income households that install new electric

appliances.

Low-income households can receive a rebate covering the full cost of a heat pump installation for space heating, up to a cap of $8,000; up to $1,750 for a heat pump water heater, $840 for an electric stove and $840 for an electric clothes dryer. If needed, this household also can receive up to $4,000 for an upgraded breaker box, $2,500 for upgraded electrical wiring and $1,600 for insulation, ventilation and sealing.

Moderate-income households can receive the same rebates covering 50% of the costs.

• Tax credits. Homeowners with household income exceeding $200,000 to $300,000 may not qualify for these rebates — if income equals 150% of area median income (see https://on.nyc.gov/3TsuhYk). For those who do not qualify for rebates, households can still enjoy a tax credit of 30% of the costs of up to $2,000 for buying a heat pump for space heating and cooling or a heat pump water heater.

More restrictive tax credits also apply to induction stoves; new windows, doors and insulation; and upgrading electricity breaker boxes. These can include both equipment and installation but are limited to $600/measure, up to $1,200/household, per year.

• Solar. Those who install residential solar panels or solar battery systems with at least 3 kilowatt-hours of capacity will qualify for a 30% tax credit, with no cap, for installations from the beginning of 2022 to the end of 2032.

• Batteries. Because it covers batteries, everyone can more easily afford a system storing cheap nighttime power for use when costs are high or can share or store some power for weather emergencies and other outages.

• Commercial. The Commercial Buildings Energy-Efficient Credit is significantly expanded to $2.50 to $5/square foot for businesses achieving 25% to 50% reductions in energy use over existing building performance standards.

• Loans. A Department of Energy Loan Programs Office provision will provide $3.6 billion to guarantee loans up to $40 billion in principal amounts.

• Developers. The New Energy-Efficient Home Credit is boosted to $5,000 to build homes that qualify for the DOE's Zero Energy Ready Homes standard. This applies to new single-family, multifamily and manufactured homes, as well as existing homes undergoing a deep retrofit.

• Building code. The legislation also provides $1 billion to support code upgrades for zero-emission buildings.

• Manufacturing. Now, $500 million is available to support domestic manufacturing of heat pumps and the processing of critical minerals; $30 billion is available as a production tax credit to accelerate domestic manufacturing of solar panels, wind turbines and batteries; and $10 billion is allocated as an investment tax credit for building new facilities that manufacture these technologies.

• Environmental justice. Funding of $3 billion will enable disadvantaged communities to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, mitigate risks from extreme heat, improve climate resiliency and reduce indoor air pollution.

• Affordable housing. This provision includes $1 billion in grants and loans for retrofit projects that advance building electrification, and improve energy and water efficiency in affordable housing.

• Tribal electrification. Includes $145 million to help tribal communities transition to clean, zero-emission, electric energy systems.

• Methane. A new fee for emitters of up to $1,500/ton of this potent greenhouse gas in 2026.

• Electric vehicles. A $7,500 credit for new electric vehicles (EVs), $4,000 for used EVs and $1,200 for home chargers. This will help more people to afford an EV and save money every month. Credits do not apply to sedans more than $55,000 and SUVs/trucks more than $80,000, as well as if the buyer’s income exceeds $150,000 for single filers and $300,000 for joint filers.

Car buyers who owe very little in taxes can assign the credit to their dealership, which might pass the subsidy back to the customer.

Infrastructure, Jobs and Manufacturing

The IRA bill was preceded in November 2021 by the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, which activated hundreds of billions of dollars for program extensions or new money for clean energy infrastructure, clean drinking water and high-speed internet.

It included $55 billion to expand clean water access and replace lead lines for households, businesses, schools, child care centers, tribal nations and disadvantaged communities. It allocated $65 billion for energy grid upgrades through thousands of miles of new, resilient transmission lines to lower costs, expand renewables, and improve cybersecurity and extreme weather resistance.

It provided $7.5 billion to build out a national network of EV chargers, guaranteed $89.9 billion for public transit over the next five years, $66 billion to expand passenger rail and $65 billion to expand broadband. It also set aside $50 billion to protect against droughts, heat, floods and wildfires; and $21 billion to clean up Superfund and brownfield sites, reclaim abandoned mine land and cap orphaned oil and gas wells.

As a reminder, the American Innovation and Manufacturing Act was also enacted by Congress in December 2020. It directs the EPA to phase down the production and consumption of hydrofluorocarbons, maximizing reclamation, minimizing releases from equipment and facilitating the transition to next-generation technologies (natural refrigerants) through sector-based restrictions. This addresses ozone layer and climate problems.

Seattle Kraken’s Climate Pledge Arena

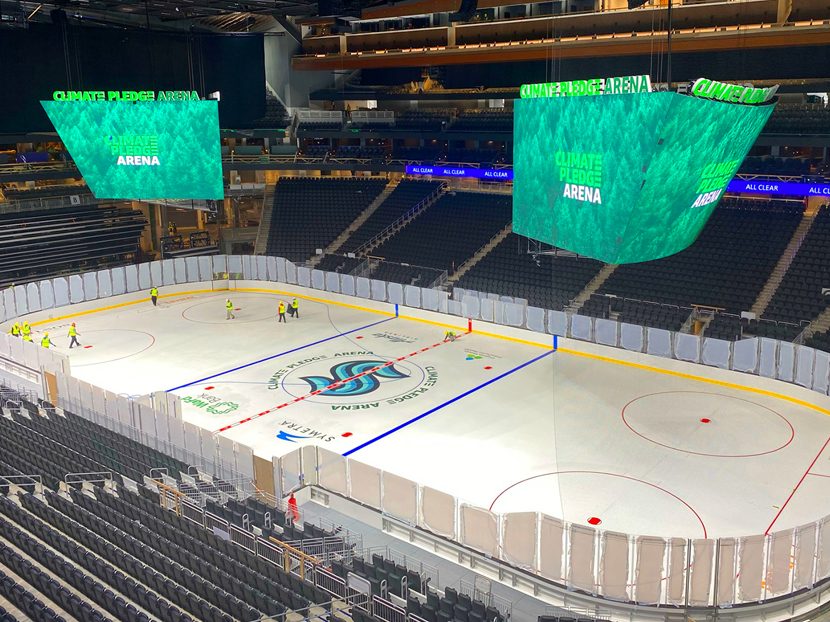

By the time you read this, 32 NHL teams will be preparing to take to the ice for another season of supersonic skating, slick plays, impossible goals, heroic saves and brutal bodychecks. The league has been around for more than 100 years, but one of its teams, the Seattle Kraken, has only existed for one year. It’s new, and so is its shiny, ultra-modern, climate-friendly arena.

Given the recent unprecedented greening of America, it is appropriate that the newest hockey palace is the “first NHL arena named for a cause rather than a company,” says Mohit Mehta, principal at ME Mechanical Engineers of Colorado, who designed the HVAC and other mechanical systems on the project. The rights were, in fact, purchased by Amazon, which then named it after the corporation’s own environment program.

Climate Pledge Arena is actually an extremely deep retrofit of a historic 1962 World’s Fair building used to showcase futuristic cars and, later, to host various city events. The massive concrete roof was designated as a local, state and national historic landmark and could not be removed or significantly modified. This became an environmental plus because using the existing structure reduced embedded carbon, but also a challenge because solar panels had to be mounted elsewhere.

Continuing the embedded carbon theme, designers decided to dig down 60 feet, sinking much of the structure below grade, which also reduced the amount of new material (and insulation). Some of the single-pane glass had to be left untouched, too. This might also have been difficult; however, Seattle enjoys a relatively temperate climate, so the building envelope was somewhat less significant when planning the first certified zero-carbon arena in the world.

Seattle is also rainy, which meant that an ambitious rainwater reclamation system made sense. The arena’s “Rain to Rink” system harvests water off the roof, collects it in a 15,000-gallon cistern, and reuses it for making the ice on which the players skate. The project included heat reclaim from icemaking, big new stormwater runoff tanks, heat pump water heaters, waterless urinals, ultra-efficient showers and water bottle filling stations throughout the arena.

No Fossil Fuels

None of the 800,000-square-foot structure’s HVAC systems or cooking facilities use fossil fuels. In our interview, Mehta says that designing for electric or induction cooking for more than 17,000 fans was possibly a more significant achievement than going green with the HVAC.

The latter involved heat pumps, dehumidification (most of the time) and electric boilers, which still might be considered a pricey option on some projects. However, it made great economic and environmental sense for this project and in the state.

“Our local grid is pretty green,” Mehta says; it’s mostly hydro and increasingly utility-scale solar farms. “Sadly, the team didn’t make it into the playoffs in their first season; however, it allowed more access for us during the summer to continue reviewing data and understand the most efficient ways to operate the new building.”

Climate Pledge Arena is a commercialized entity also used for basketball and concerts; therefore, the plan included some highly visible environmental efforts. It features a huge living wall in the mezzanine, everything is recycled and recyclable, event tickets are all electronic, and hockey tickets are paired with free city transit passes for travel to and from the event.

A House in Frigid Minneapolis

As described in the foregoing, recent acts of Congress have codified in law that going green in America is not only for wealthy people or big projects. The new measures support commercial projects such as Seattle’s new arena, plus industrial, institutional and residential projects, big and small.

The main reason we need rebates and tax credits to spur green behavior is that we seem to prioritize short-term cash in hand over long-term savings. If we didn’t, we would realize that almost all clean energy systems eventually pay for themselves and more by saving money over time.

One American didn’t wait for the recently announced incentives because he has long understood in detail how he could save cost by electrifying his small home in Minneapolis, Minn. His name is Gary Nelson and he is the owner of The Energy Conservatory, which sells blower doors and other technology used to create low-carbon

buildings.

Nelson’s 1,700-square-foot house is pretty tight, well-sealed with modern triple-pane, argon-filled, low e-coating windows, insulation at R30-R40 and 1.0 air change per hour at 50 Pascals.

Four Minneapolis winters ago, he installed a Fujitsu ducted mini-split heat pump with a capacity of 18,000 BTU/hour and no backup heating system. “The heat pump water heater is located in the same room and the energy recovery ventilator also dumps in there, so the mechanical room is like a big return plenum,” Nelson says. He also owns an Ultra-Aire dehumidifier.

Nelson has proven that heat pumps work in cold places. The winter of 2019-20 wasn’t very cold, but the other three winters had some frigid stretches. In 2017-18, the low in Minneapolis was -15 F. Although the outdoor temperature went 5 degrees below the design temperature, the heat pump held the house at the 72 F setpoint.

In 2018-19, the outdoor temperature went down to -27 F. The indoor temperature hit a low of 62 F. He calculated that the heat pump capacity was 8,597 BTU/hr. (2.52 kilowatts), power consumption was 1,834 watts and the coefficient of performance (COP) was 1.37. When the temperature rose to -17 F, the COP was nearly 2.0. However, they were out of the country that year; Nelson thinks they probably could have gotten the house up to the setpoint with body heat and cooking.

In February 2021, they had a few nights down around -17 F at night and not much sun in the daytime. The heat pump ran flat out for three or four days. On the third morning, Nelson turned on the electric oven for about an hour with the door open and then set it to 350 F with the door closed for the rest of the day. They used about

40 kWh of resistance heat.

Americans now have the proven systems and government support we need to manage planet-friendly heating, cooling, refrigeration, cooking, clothes drying, transportation, manufacturing, power generation, electricity storage and more in cold, warm and humid places, in small homes, big arenas and everything in between. Welcome to the future. Welcome to the clean energy age.