Big Data and the Flint Water Crisis

Researchers used connections and patterns hidden in data to provide better solutions to the city’s problems with lead contamination.

Most of us have fallen back a time or two, particularly when we’re teetering on the direst of straits, on that old reliable WAG — the “wild ass guess.”

Now, however, “Big Data” and algorithms can quickly untangle our gut feelings and, more times than not, accurately predict the best answer from many likely outcomes. As a result, we’ve moved up to the much more intelligent-sounding “educated guess.”

In September, researchers at the University of Michigan said that these data analytics methods, such as those employed by Facebook and Amazon, can help solve lead contamination issues in Flint, Mich.

“But whereas Facebook’s algorithms crunch through uploaded photographs to detect faces and Amazon’s models predict which products you’ll like, we are using these analytics tools to detect homes with high risk of lead contamination and to predict the locations of lead pipes buried underground or hidden in the homes of residents,” said the research duo of Jacob Abernethy, assistant professor of electrical engineering and computer science, and Eric Schwartz, an assistant professor of marketing.

The professors aided by students aggregated a trove of available data around Flint’s water issues, including water test results, records of the service lines that deliver water to homes, information on parcels of land and water usage.

Flint Water Crisis

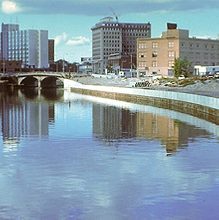

Briefly, the Flint Water crisis began two years ago, when the city's drinking water source was changed from Lake Huron via Detroit's water system to the Flint River. The new water supply, not properly monitored for corrosion control, caused lead to leach from service lines into the city's drinking water. While the Flint has since switched its water supply back to the Detroit system, its 102,000 residents are still being advised not to drink unfiltered tap water.

Lack of useful information and understanding of locations most at risk for lead contamination remains a difficult challenge. Only about 30 percent of homes in Flint, for example, have had their water tested, and city officials have had to rely on decades-old, hand-drawn plot maps to identify homes most at risk.

By leveraging algorithmic and statistical tools, however, the Michigan team says it’s been able to produce a more complete picture of the risks in Flint.

“Our guesses aren’t perfect by any means, but estimates of this level can save millions of dollars on recovery efforts,” according to the initial investigation.

There are essentially three main components to what the research has found so far:

Where is the lead?

That the service lines may not be the only driver of lead in Flint’s drinking water is certainly the biggest surprise of the initial findings.

“Yes, it is the case that those homes with copper service lines have lower lead levels, on average, than those with lead in their service line,” the research says. “But when you look closely at the water-testing data, the differences are much smaller than you might think.

Large spikes of lead occur in homes with and without lead service lines, according to the research.

"This suggests a large fraction of the dangerously high lead readings are probably not being driven by the service line material but instead by other factors," the researchers write. "Civil engineers who study these problems report that lead can leach from several sources, including the home’s interior plumbing, faucet fixtures and aging pipe solder."

Earlier this year, Flint officials began its FAST Start program using more than $27 million in state-appropriated funds to remove lead-tainted service lines, but the progress has been slow going. So far, 33 lines have been replaced, and the next phase of the initiative is now under way in which as many as 250 lead-tainted pipes could be replaced.

Meanwhile, the city could have more than 10,000 pipes composed of either lead or galvanized steel contaminated by lead that need to be replaced, according to preliminary estimates.

"What we can conclude is that citizens as well as policymakers may need to widen their focus beyond the service line materials and consider alternative efforts to address other sources of lead," the professors wrote. "Service line replacement is certainly a necessary part of the solution, but it will not be sufficient."

Where is the piping?

The researchers still conclude service line replacement is part of the solution, but the immediate challenge with this work is the most obvious: Where are those pipelines?

“The city, unfortunately, did not maintain consistent records on service line installations and materials,” the two researchers write.

Their work mentions Martin M. Kaufman, a geography professor at the Flint campus of the University of Michigan, and the work he’s done on “big data” from a very different era – digitizing hand-written annotations on a set of plot maps. In some cases, but certainly not all, the maps include what type of metal was used to connect water to most every home built in Flint.

Kaufman's research focused on mapping the thousands of different water lines in Flint to see what areas have the highest number of lead pipes in them. His team found there are 4,300 service lines made of lead, 25,000 made of copper, 11,000 made of galvanized material, but 13,000 were left “unknown,” meaning they could be made of lead.

City records were not available for those 13,000 homes, so Kaufman and his team used data to predict whether or not the home is likely to have lead piping based on surrounding homes and when it was built.

The new research built onto Kaufman’s work to try to fill in the missing information.

Abernethy and Schwartz gathered all the available city data, parcel records and a database of more than 3,000 inspection reports. With this, “machine-learning techniques” were able to seek patterns in the existing records and predict the type of material in a home's service line with 80 percent accuracy.

“Looking for patterns in the existing records, statistical tools can provide a reasonable ‘educated guess’ as to the type of material in a home’s service line,” says the research.

Abernethy and Swartz’s team have also been on the ground working with retired National Guard Brigadier General Michael McDaniel, who is heading up the line replacement program, providing these statistical estimates to better target replacement resources.

Where are the homes?

Another way to identify the location of the affected piping is to consider what the addresses of the affected homes might be. While the headlines on Flint could leave readers to believe all homes in the city have dangerously high levels of lead, that is not the case.

In February, for example, only between 8-15 percent of homes had lead above the federal action level of 15 parts per billion, according to an analysis of state testing. State testing through August indicated lower lead levels found in the city and fewer number of homes exceeded federal guidelines.

“Based on about 750 homes monitored repeatedly, fewer homes have tested above the action level over time,” according to the research. “Almost half of all samples have virtually no detectable level (below 1 parts per billion).”

Granted, these figures come at a time when things were improving in Flint after water was sourced back to the Detroit municipal system.

Still, "these low numbers provide little comfort when we don’t know which homes are still at risk," the team wrote. Only three out of 10 homes in Flint have had their water tested, according to government data, and these tests “do not guarantee safety; they only identify danger."

So how can these homes be better identified? First off, the team says its work in this area is only “to a modest degree of accuracy.”

However, the team built statistical models based on several attributes, such as year of construction; location; value; and size, to conclude an estimate of risk level.

“The quality of these models is driven by the huge swaths of data from water samples submitted by residents and tested by government officials in response to the crisis,” says the research, adding that the data covers approximately 10,000 homes from November 2015 to the present.

Perhaps not the most surprising, the data suggest that the older the home and lower its value the greater the risk of lead. In addition, while the highest reading are geographically scattered, “the home predicted to be at high risk tend to cluster in specific neighborhoods,” says the research.

The unfolding story in Flint has left people across the country wondering if lead poisoning is a problem in their own community.

“Toward solving the broader problem, data and statistical tools can help greatly reduce risks at much lower cost, and a data-oriented understanding of the problems in Flint can guide efforts to address lead concerns in other regions as well,” says the research.

There’s an app for that

Considering the approach taken by the research, it should not be a surprise that a $250,000 donation from Google.org, the company’s charitable arm, helped underwrite the project.

About $150,000 was earmarked for the University of Michigan’s research, which also included creating an app with the relevant risk assessments. (The remaining $100,000 was given to the Community Foundation of Greater Flint for the Flint Child Health & Development Fund, which focuses on the long-term health of Flint families and children from newborns to 6-year-olds.)

“Access to clean drinking water is a concern all over the world, but in the United States it’s often a foregone conclusion,” Mike Miller, head of Google’s Ann Arbor, Michigan office, wrote in a blog post. “That is not the case recently for the residents of Flint, Michigan. It’s a crisis, one to which the American people readily responded by donating water and resources to help alleviate the immediate pain,” he added. “But the problem won’t go away quickly and understanding its extent is both challenging and an absolute necessity.”

The donation supported student researchers on the university’s Flint and Ann Arbor campuses, in particular the members of the Michigan Data Science Team, an extra-curricular group founded by Abernethy.

The work was purposefully designed to keep the data tools they develop flexible so that other cities faced with similar crises as Flint could put them to use.