Buffer Tanks

These under-used components of today’s hydronic systems virtually eliminate boiler short-cycling and premature failure of other parts.

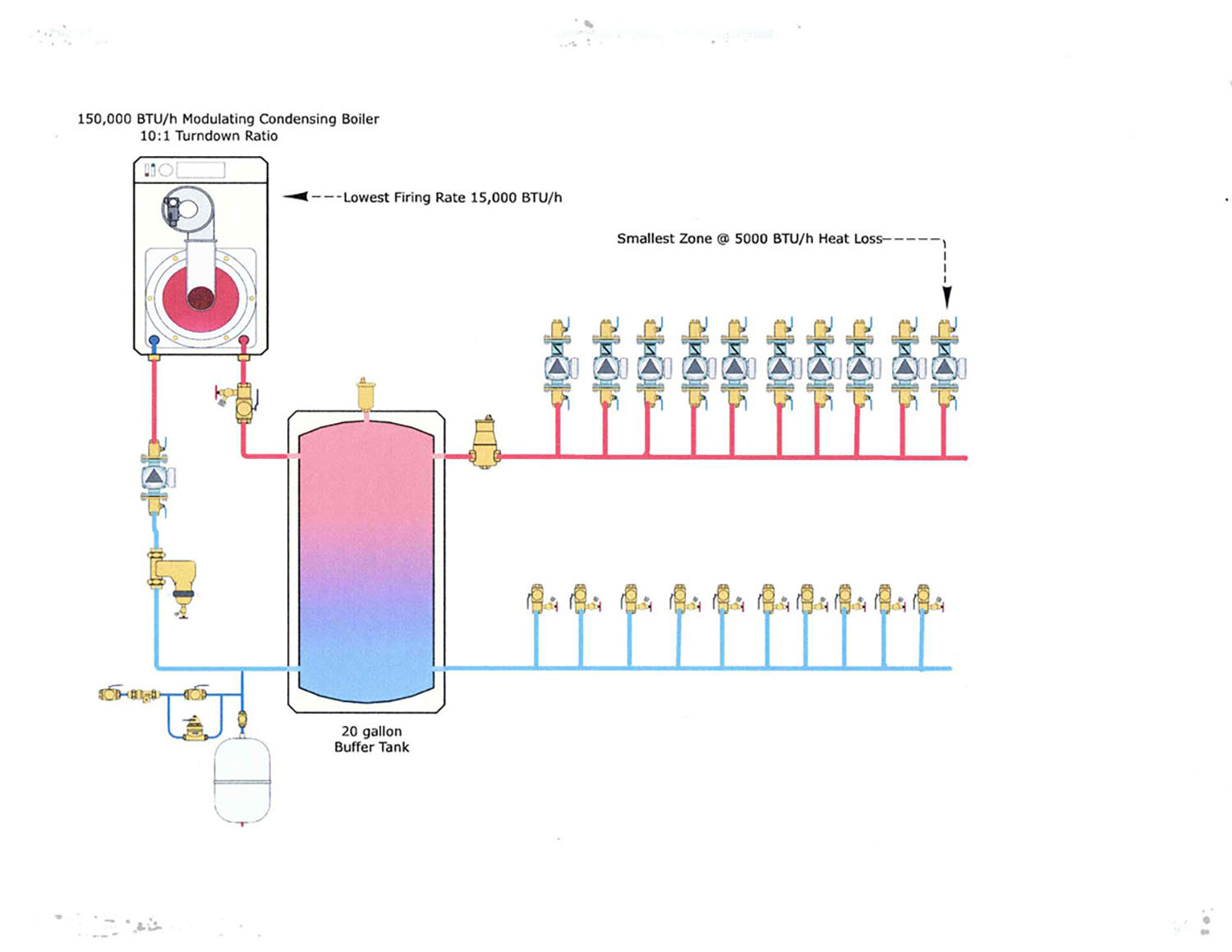

What’s the first thing you think of when you see the setup in the image above? Awesome piping? Impeccable workmanship? Stellar selection of components? Hydronic Wall of Fame material?

I’d be thinking of something entirely different. Every time I look at one of these multizone projects on LinkedIn, Instagram, Twitter, Facebook or upfront and personal, I’m looking for the buffer tank and wondering: Is the boiler short-cycling? Does this system need a buffer tank? What’s the boiler size and turndown ratio of the modulating-condensing boiler? What’s the heat loss of the smallest zone? Did the designer even consider a buffer tank?

I call it my self-induced hydronic anxiety.

I’ll answer all those questions and more because a flawlessly piped system doesn’t always translate into a system that runs efficiently.

Consider where we were 20-some years ago compared to where we are today in terms of boiler selection. We went from residential, cast-iron boilers with high thermal mass heat exchangers that held anywhere from 12 to 20 gallons of water, to relatively low thermal mass heat exchangers that only store 2 to 5 gallons of water.

Yet, the firing rates stay the same, of course. A 100,000 BTU/hour modulating-condensing boiler will heat 4 gallons of water a heck of a lot faster than a 100,000 BTU/hour cast-iron boiler can heat four times the amount of water. Quite the mathematician, aren’t I?

It really hits home, though, when you think about it in those simple terms. We need to consider how it affects boiler operation and the cycle rate of the burner. A mod-con boiler will to produce heat much faster than the heat emitter can release that same heat.

The result is the burner will hit the boiler control’s target setpoint many times over before the thermostat’s call for heat is satisfied. Those 4 gallons of water are going to come up to temperature very quickly, resulting in on/off cycles in rapid succession.

Short-cycling is the bane of every mod-con boiler’s existence. Combustion efficiency suffers, and every component of the boiler will be put through thousands and thousands of unnecessary cycles, resulting in early failure. You’ll likely hear about those short burner cycles from your customers.

Well, I’ve got good news for you. There is a solution — a buffer tank. I like peace of mind and buffer tanks give me that. I never want somebody coming back to me and saying their boiler is screwed up and I’m the reason for it.

Buffer tanks are simply a container of water that can be piped in a two-pipe or four-pipe configuration. They’re very well-insulated compared to any boiler heat exchanger and available in many sizes from many manufacturers.

How do you know if you need one? And how do you size one? Good questions.

First off, you’re not likely going to need one in smaller homes because those are typically one or two zones. It’s the larger homes where the customer wants and needs every bell and whistle — including independently zoned master bathrooms and walk-in closets.

No matter how much you try to convince them that 17 zones may not be in their best interest, they’re having none of that nonsense. They want what they want, and nobody is going to tell them otherwise.

My method of operation was to give them what they want, so long as they didn’t get in my way of designing it properly. And because of those microzones they’re insisting on, I’m insisting on using a buffer tank. We both get what we want in that regard.

Sizing a buffer tank

Almost any manufacturer that makes buffer tanks also provides an app on how to size them. You plug in the numbers, the app spits out the number of gallons the tank capacity should be. Simple enough, but you need to calculate those design values, so you may as well take it through to this final stop using some very basic math.

Below you’ll see the formula, the meaning of the formula's values, and an example of how to size the buffer tank. It’s always the zone with a 5,000 BTU/hour heat loss that will cause you problems.

Desired Run Time x (Minimum Boiler Output – Minimum System Load) = capacity in gallons

System Delta T x 8.33 x 60

• Desired run time (minutes). The desired amount of sustained firing time of each run cycle once a call for heat is initiated. A minimum of 20 minutes is a good place to start.

• Minimum boiler output (BTU/hour). Based on the boiler’s minimum firing rate, the output of the boiler is determined by its turndown ratio, AFUE and input BTU/hour.

• Minimum system load (BTU/hour). The heat loss of the smallest zone.

• System design delta T. The design temperature difference across the system at minimum load.

• 8.33 (pounds). A fixed value of the weight of one gallon of water.

• 60 (minutes). A fixed value of minutes in one hour.

To calculate the buffer tank capacity for a 150,000 BTU/hour mod-con boiler with a 10:1 turndown ratio:

• The minimum boiler input is 15,000 BTU/hour (150,000 ÷ 10).

• The minimum system load is 5,000 BTU/hour (smallest zone).

• The system delta T is 20 F (based on the type of system).

• And the desired run time is 20 minutes (never less than 10 minutes).

20 x (15,000 – 5,000) = 200,000 = capacity of 20 gallons or more

20 x 8.33 x 60 9,996

Taking the time to plug these values into the equation will give you your 20-minute run-time cycle. You choose the desired run time, but I would not suggest going lower than 10 minutes, which will provide you with six cycles an hour. I prefer a 20-minute run time, which results in three cycles each hour. Any lower is outside my comfort zone.

Hydronic system upgrade

Upgrading a hydronic system using a buffer tank is almost always an easy one to sell, even to the toughest of customers. The buffer tank will serve as a hydraulic separator, so you can remove it from the material list. The added water — the thermal mass — will be insulated better than any boiler I’ve ever seen. You’ll rule out short cycling due to poor design. The buffer tank also can provide some temporary heat during a maintenance call or other service-related issues.

Figure 2 is another photo of that same job. It answers the question of whether a buffer tank was used.

And Figure 3 is a typical piping schematic using a four-pipe buffer tank. We’ve all seen these jobs: Lines of circulators or zone valves that used to be connected to a large cast-iron boiler but now connect to a modulating-condensing boiler. Sixteen gallons of thermal mass down to a measly 4 gallons of thermal mass.

Without the added buffer tank, that new boiler will bang on and off all day long, all week long, on and off, on and off — resulting in the premature failure of ignitors, the combustion blower and other components. Not to mention the fact that every time the mod-con burner fires up again, it has to ramp back up to a 100 percent firing rate before settling into a lower fire. It’s the very definition of poor design and inefficiency.

The buffer tank may be the most under-used component in the design and installation of today’s hydronic systems. As an industry, I believe it’s in our best interest to use them more than we do. Knowing and understanding these terms and parameters — and how they factor into the sizing of a buffer tank — will make it much easier for you to add this invaluable tool to your installations and designs.