Cooling Towers and Legionella Primer; Where Are We Headed?

What do lawn darts, seat belts and cooling towers have in common? They have all been subjects of epidemiological studies. Epidemiology is the branch of medicine which deals with the incidence, distribution and possible control of diseases and other factors relating to health. I was fascinated when my wife, Kristy, explained to me that we could thank epidemiological studies for requiring seat belts in cars and the banning of lawn darts.

I was even more fascinated to learn about Legionnaires' disease and Pontiac fever, and why HVAC systems can be such a breeding ground for them. Legionnaires' disease can only be contracted by the inhalation of aerosolized water contaminated with the Legionella bacteria. Cooling towers aerosolize water and they're everywhere.

The International Association of Plumbing and Mechanical Officials has been protecting the public's health and safety for 93 years by working in concert with government and industry to implement comprehensive plumbing and mechanical systems around the world. Having served on technical committees with IAPMO since 2015, I joined a task group to develop recommendations and guidance to assist in the control and intervention of Legionella associated with mechanical systems.

My wife and I decided to put our combined efforts into the Legionella Task Group. While our first meeting with the task group was March 2, 2020, we started studying The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention records as early as January. Kristy has quite a head start on me since she's a registered nurse and in her second year of public health/epidemiology studies at Brigham Young University.

For a quick history, Legionella was discovered after an outbreak in 1976 among people who attended a Philadelphia convention of the American Legion. Those who were affected suffered from a type of pneumonia (lung infection) that eventually became known as Legionnaires’ disease. Public health professionals raced to trace the origin of the disease.

The first identified cases of Pontiac fever occurred in 1968 in Pontiac, Mich., among people who worked at and visited the city’s health department. It wasn’t until Legionella was discovered after the 1976 outbreak in Philadelphia that public health officials were able to show that the same bacterium causes both Legionnaires’ disease and Pontiac fever.

Continued Outbreaks

Recorded outbreaks of Legionnaires’ disease have grown dramatically in the decades since 1976 until now. It is unclear whether this is due to increased awareness and testing, increased susceptibility of the population, increased Legionella in the environment or some combination of factors.

In the summer of 2015, the largest outbreak of Legionnaires' disease in New York City history was traced to a cooling tower at a hotel in The Bronx (https://bit.ly/2vPlZDQ).

It was mid-July when the Bureau of Communicable Disease of NYC's Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH) detected an abnormal number and distribution of Legionnaires' disease (LD) cases in the South Bronx. The NYC DOHMH led the outbreak response, part of which included sampling numerous cooling towers within the city for Legionella pneumophilabacteria.

In the aftermath of the outbreak, NYC became the first broad jurisdiction in the United States to take a regulatory approach to the management of cooling towers to prevent Legionella contamination.

On Aug. 10, 2015, the NYC City Council introduced legislation requiring the registration of all cooling towers with the Department of Buildings and inspection at least every 90 days during times of operation. The cooling tower legislation, officially known as Local Law 77 (https://on.nyc.gov/2IBvFEx), was enacted eight days later. The outbreak was officially declared to have ended on Aug. 20.

A total of 138 cases and 16 deaths were attributed to this outbreak, making it the largest LD outbreak in NYC history.

Taking into consideration the passage of Local Law 77, we have the first required registration and treatment protocol for cooling towers. Similar regulations will likely be in the 2024 plumbing and mechanical codes for consideration of adoption by state and local jurisdictions.

Outbreaks of Legionnaires’ disease are more common than we may realize. In July 2019, an LD outbreak occurred at a Sheraton hotel in Atlanta that initially infected six guests (https://bit.ly/3a7yNEx). After a complete Georgia Dept. of Health investigation returned positive cooling tower and atrium fountain specimens, another 14 cases were confirmed and one death resulted.

The number of reported health-care-associated (HCA) Legionnaires' disease cases seems to be rising (https://bit.ly/2v8IPWI). The Covenant Living retirement home health-care system is a multifacility corporation with LD outbreaks at different facilities. These have resulted in a combined number of 16 confirmed cases of LD, with two deaths. Each case was positively matched to a strain of the LP bacteria samples that were found in the potable water system (https://bit.ly/2UiYdby).

Concerns about Cooling Towers

According to the CDC, HCA Legionnaires' disease has a mortality rate of more than one in four (https://bit.ly/2TwIOVU), which is much higher than that of the general public, making the management of water systems in health-care facilities an urgent concern (http://bit.ly/2Ae6Cq6).

If you Google "Legionella outbreaks in cooling towers" and click on the "News" tab, you're going to find many recent stories of LD outbreaks, especially in the cooling seasons.

Since the newly instituted LD regulations for Veterans Affairs and the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare have become more media mainstream, questions and conversations about the safety and efficacy of cooling towers are beginning to take place (https://bit.ly/3adBB36).

At San Quentin back in 2015, when eighty inmates were found to have been infected with Legionnaires’ disease and the bacteria was traced back to the health services HVAC cooling tower (https://nyti.ms/33xwbNP). When asked about the maintenance protocol, there was no record of checking or treating for Legionella pneumophila, nor did the EPA inspectors’ which cleared the cooling tower just 2 months before the outbreak.

Fast forward to the spring of 2019; California thought that its days of dealing with Legionnaires’ disease were far behind them. In April 2019, the state had yet another LD outbreak, only this time it was in Stockton prison and spread quickly to two nearby youth correctional facilities (https://lat.ms/33DwpTp).

Unlike the San Quentin outbreak, this was an infection of the potable water system, an aging infrastructure that required bottled water and portable bathrooms and showers be brought in for weeks until the outbreak could be declared over. In the end, 29 cases of Legionnaires’ disease were detected and one death.

Cooling Tower Research

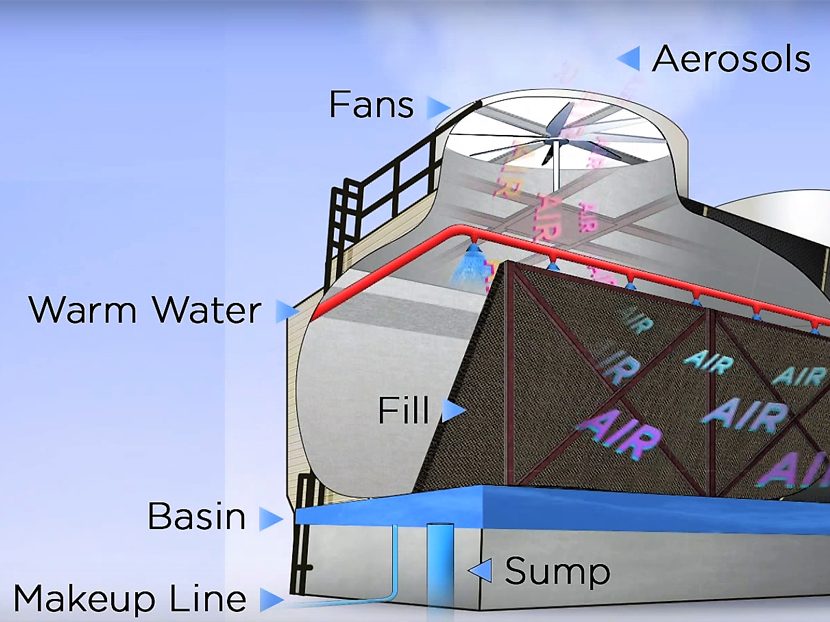

To understand how cooling towers work, take a look at these YouTube videos: cooling tower basic operation (https://youtu.be/pXaK8_F8dn0) and a chilled water system with cooling tower (https://youtu.be/1cvFlBLo4u0).

Cooling towers are capable of dispersing aerosolized water droplets onto adjoining property as far as 300 to 400 meters (Dyke, Barrass, Pollock and Hall, https://bit.ly/2TOCYhx).

Cooling towers have reservoirs in which hydrophilic bacteria such as Legionella pneumophila, pseudomonas aeruginosa and many others that will only be added to antimicrobial resistance in the coming times (Berjeaud et al., https://bit.ly/2TBkoKV).

Some of a cooling tower's fallibility is based on its inherent design. The fact that it allows even a small amount of water to remain standing increases the likelihood of biofilm growth, which protects and enhances the proliferation of Legionella pneumophila, along with its many common Legionella cousins (Crook et al., https://bit.ly/2Q26oYn).

Once the bacteria have used the biofilm to cling to the wall of the pipe, they can replicate. When the time and temperature are right, they may be dispersed through aerosolized water droplets into the air. Factors associated with amplification include warm water temperatures (77 F to 108 F (25 C to 42°)); water stagnation; the presence of scale, sediment and biofilm in the pipe and fixtures; and the absence of disinfectant.

Using Geothermal Instead

Like many products, cooling towers perform an essential service but have a distinct risk factor that is managed only by sound maintenance practices. Many may consider the risk too high and may wish to remove the root cause altogether. One of the best ways to eliminate the possibility of Legionella exposure from cooling towers is to eliminate the cooling tower.

Geothermal exchange systems solve this concern while at the same time providing the ability to eliminate combustion heating. Geothermal exchanger-sourced buildings fit the world-wide model of sustainability perfectly. A geothermal building uses less energy than any other HVAC system, whether equipped with central chiller plants or distributed heat pumps.

They use renewable energy, pumped to and from the earth, eliminate on-site combustion heating, and eliminate freshwater consumption related to cooling tower operation. With no cooling towers, the regular monthly chemical maintenance and cleanings are eliminated. The threat of a Legionella outbreak from cooling towers is eliminated.

Curious about what will work for your application? Watch "Introduction to Geothermal Systems Technology" from the International Ground Source Heat Pump Association, the Geothermal Exchange Organization, or just email me at jayegg.geo@gmail.com

CDC Resources

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention offers additional information at these sites:

- CDC, history of Legionnaires' disease, www.cdc.gov/legionella/about/history.html

- CDC, YouTube video, lecture on discovery and history of Legionnaires' disease, https://youtu.be/ALZyly9_l4w

- CDC, Legionella guidelines and standards, www.cdc.gov/legionella/resources/guidelines.html

- CDC, YouTube video, engineering for Legionnaires' disease outbreaks, https://youtu.be/RV0bmdliQjQ

- CDC, YouTube video, Legionella testing guidance for cooling towers, https://youtu.be/sye-CwertMA

- CDC, water management and prevention of Legionnaires' disease, https://bit.ly/3bj3RkQ