Accelerating Small-Business Development

The ultimate necessity of unitary business direction can be enhanced by digital technology that is ready to be used.

According to Thomas J. Donohue, CEO of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, “small independently owned businesses” are the backbone of American industry. He further believes that digital technology will accelerate their economic growth.

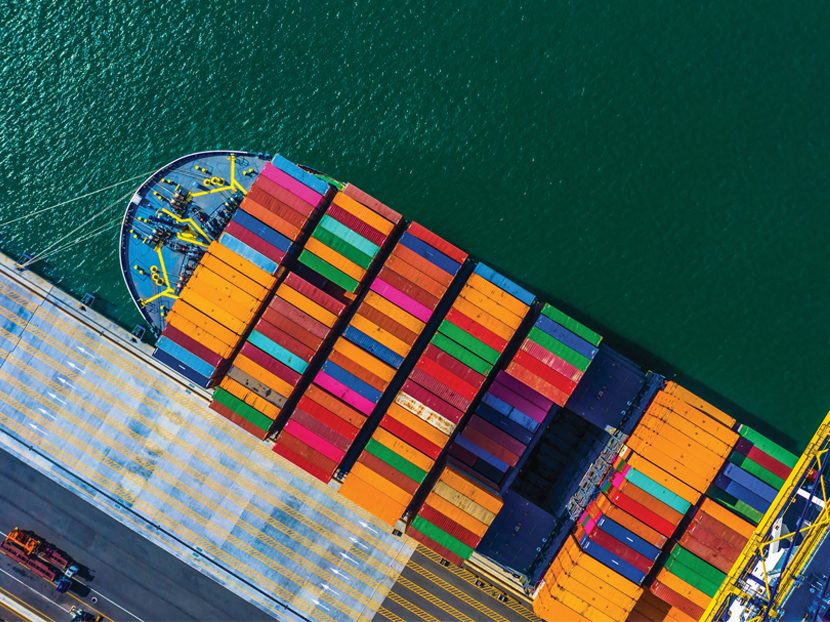

To help realize such potential expansion, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce publicized a report detailing the impact of such technology on small business exports. In a survey of more than 3,800 nonfarm small businesses that have never focused on the potential of exports, it found that small business exports already produce substantial results for the U.S. economy, generating $541 billion annually, and supporting more than 6 million jobs.

But only 9 percent of small businesses sell their goods or services abroad. It is believed this is a potential that can be implemented by a combination of private and public sectors removing the restraints that now exist. These include foreign regulations, tariffs, customs producers and payment collections. Such facilitation could add 900,000 jobs to the U.S. economy, according to the U.S. Chamber of Commerce.

But tearing down regulatory barriers to trade is only part of the battle. The other half is equipping small businesses with the digital tools they need to succeed in a global economy.

Unfortunately, 73 percent of small businesses interviewed their top executives and indicated limited involvement with these opportunities. They include accessing foreign markets, which encompass digital translation services, cross-border electronic payments, website localization, and a wide range of other export-oriented resources.

Donohue goes on to emphasize how vital such small business exports can be to the American economy in general. Thousands of privately-owned small businesses could be broadening their base to encompass exports, even if only including such expansion into Canada, Mexico, Central America and South America. This facet under private control would also solidify this aspect of privately owned business holdings.

Unfortunately, it will take the initiative of private leadership to make this happen. In personal contact with such business owners, we tend to hear the negatives of a self-imposed sense of inferiority in competing with the huge industries. These are now controlling the export/import aspect that has reached a record monetary volume since the first two decades of this century.

The ultimate necessity of such unitary business direction can be again enhanced by digital technology that is ready, willing and able to be used. Such utilization will prove whether such ingenious private business desire still exists today.

Oil Production Downturn

Since America’s first modern oil well was drilled in Western Pennsylvania in 1859, both its maximum fracking production and domestic/export consumption have reached new heights.

But with the 2020 presidential election becoming ever more focused, the Democrats have made part of their platform — the decreasing usage of oil, coal or any of the lesser energies that belch carbon dioxide into the air. This is further heightened by those politicians and others who believe that maximum reduction is urgent if we are to reverse the fouling of the Earth’s climate.

But major U.S. oil firms claim that America’s production will still reach over 95 million barrels per day, and then plateau. But output will need to drop to 45 to 70 million barrels per day to keep the global fouling from further climatological damage. This projection has already instigated less long-term capital expenditures and more emphasis on short-term projects.

Although remaining an indispensable fuel for automation and other critical economic categories, electric cars and electric engines are making themselves felt with the knowledge that oil may well be on the way out.

If demand does fall, as it inevitably will, some products and producers are more vulnerable than others. Over a third of all oil is used in automotive vehicles of all types. But it is harder to find a substitute for the oil in petrochemicals and plastics. It would be realistic to expect the highest cost and “filthiest” oil firms to shut their doors first.

It’s evident that this, one of America’s most essential and fast-growing industries for more than 160 years, will shrink rapidly to a small core of major producers with the highest residual demand, and the lowest financial and environmental costs.

Most environmental activists fear this “climatic impurity” energy will never happen. But it equates with Aramco’s strategy and sales pitch to its current substantial financial market appeal. No one denies that increasing climate control is desirable. But a shrinking oil industry could mean more, not less turbulence for global energy markets and geopolitics.

Downsizing an industry with $16 trillion in capital and more than 10 million employees is destined to be anything but smooth. Because oil fields naturally deplete, a drought in capital could cause a price hike.

Each firm, including national firms controlling them, with Saudi Arabia out front, will have to choose by holding back supply and closing the “market taps.” Secondary oil producers, such as Algeria, Brazil, Canada, Nigeria and Venezuela will likely be hit hardest due to their inflexibility, while Saudi Arabia, Russia and the United States will likely remain strong. However, America’s fracking boom could be short-lived as the international oil industry shrinks.