35 Generations in the Making

What is next for the Department of Interior?

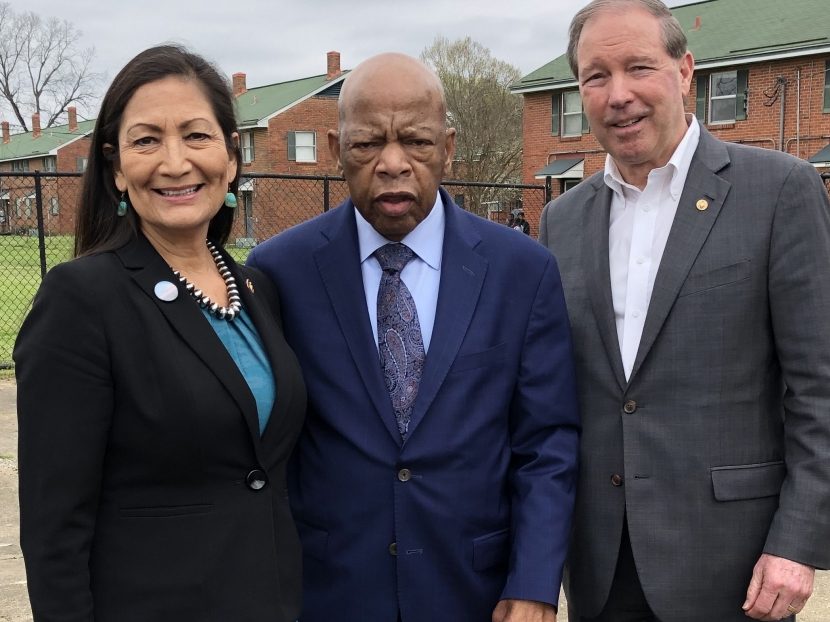

U.S. Rep. Deb Haaland, representing New Mexico’s first congressional district, was nominated as the next U.S. Secretary of the Interior, making her the first Native American to hold a cabinet position. What perspective will she bring? How will she contribute to controversial energy conversations? More broadly, how does the Department of Interior (DOI) as a whole affect energy exploration?

Haaland currently serves as the vice-chair of the House Committee for Natural Resources, but her work in the public lands sector is extensive. She previously served as a tribal administrator and vocal advocate for Native American rights. Long before that, according to Outside Magazine, she started her own salsa company in the ’90s to pay the bills (http://bit.ly/3nK0NUH).

More recently, Haaland cooked green chili and tortillas for protesters at the Dakota Access Pipeline protests. A woman who has been at the front lines of native affairs is slated to have one of the most important roles in how this country moves forward with hot-button fossil-fuel exploration on public lands.

What is the DOI responsible for? The department manages the Bureau of Land Management, the US Geological Survey, the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the National Park Service. In short, the federal agencies that make major decisions about public and tribal lands will report to Haaland.

The selection of Haaland is historic due to her background. “Haaland is a member of the Laguna Pueblo and, as she likes to say, a 35th-generation resident of New Mexico,” The Associated Press reports (http://bit.ly/35JmJcj). “The role as Secretary of Interior would put her in charge of an agency that not only has tremendous sway over the nearly 600 federally recognized tribes but also over much of the nation’s vast public lands, waterways, wildlife, national parks and mineral wealth.”

Historically, DOI heads rarely aligned with Native American interests. The Bureau of Indian Affairs once created policies to assimilate native children into boarding schools that forbid their native languages.

Today, the bureau has a diverse leadership mix, with more than 50 percent native employees. While the bureau once attempted to sweep away native culture, it has evolved into a better policy advocate for the tribes since they are majority managers. The forthcoming secretary will springboard these interests up the federal organizational chart.

Haaland will succeed David Bernhardt, a former oil and energy lobbyist. “State offices in 2017 generated nearly $360 million from oil and gas lease sales, an 86 percent increase over the previous year's results of $192.5 million,” a BLM press release states (https://on.doi.gov/2LO56Bc). “Among these sales, which together were the highest in nearly a decade, rights to a total of 949 parcels, covering 792,823 acres, were sold.”

Bernhardt notes in the release that he will continue to roll back regulations to create jobs and revenue growth on federal lands.

Before Bernhardt, Ryan Zinke headed the agency. His colorful tenure involved a few questionable spending decisions. He is essentially known for booking expensive private travel on the taxpayer dime more often than one should, which is never. According to the AP, he also spent $139,000 to upgrade three doors in his DC office (http://bit.ly/3qlLenL).

The funniest critique of his tenure came from an Outside Magazine article, in which journalist Elliott D. Woods accused Zinke of being a fake outdoorsman because he could not assemble a fly rod correctly during their interview. “Seems like an inconsequential thing, but in Montana, it’s everything,” Woods explains (http://bit.ly/38KmQGI).

Aside from Zinke’s spending sprees, he is famous for recommending to President Donald Trump that Bears Ears National Monument and Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument be redesignated to allow for more oil and gas exploration. President Trump adopted the recommendation. Local tribes and conservationists have legally challenged the decision; President Joseph Biden may cancel new leases, in any event.

Energy exploration on public land

Returning to the question at hand, what should the Department of the Interior do in terms of energy exploration? The last two secretaries used the department to unlock national oil and gas exploration parcels, in some cases creating more jobs in rural areas and increasing tax revenue by leasing federal land.

Haaland and members of other tribes may see those same redistributions of land at the direct expense of native interests, with Standing Rock and Bears Ears as prime examples. Should the DOI protect or privatize and profit from our public and native lands?

President Teddy Roosevelt led the conservationist movement to protect and rein in egregious commercialization of public lands. Regulation was seen as important to protect the areas of our country too precious to be decimated by gluttonous logging or energy exploration.

However, Roosevelt wasn’t necessarily a strict environmentalist. He sided with Gilford Pinchot’s perspective on conservation and responsible commercialization: to “make the forest produce the largest amount of whatever crop or service will be most useful, and keep on producing it for generation after generation of men and trees.”

Teddy Roosevelt’s perspective is potentially a lost middle-of-the-road political stance. Reasonable, long-term use of natural resources was his goal. He was not in favor of unregulated energy exploration or absolute environmental protectionism.

In 2020, we can speculate what Teddy Roosevelt may have done differently, knowing what we do now about climate change and historic energy leasing on native lands. Jonathan Nez, Navajo Nation president, claims there are more than 500 open uranium mines on Navajo lands that were never cleaned up by the feds after developing weapons, according to a Washington Post interview (http://wapo.st/38KpmNa).

Future Secretary Haaland may see the DOI as a shield from irreversible damage to our remaining protected lands. About 3 percent of the United States remains designated as federal Indian reservation land, down from 100 percent before Europeans arrived.

Haaland may harbor a perspective that the time for “reasonable exploration of public lands” has long passed. At a minimum, she will provide an insightful answer when the question is asked for a new federal land lease — “At whose expense?”