Engineering Project Manager’s Guide to DHW Distribution Systems

Project documents can be challenging to navigate, so it is essential to simplify the design to the core elements that can be easily referenced.

The transition from an individual contributor to a manager requires a few new skill sets. One crucial skill is the ability to review and present work performed by others. While presenting one’s own work may not be challenging, presenting someone else’s work with the same confidence and apparent level of knowledge requires new approaches.

This column aims to provide valuable insights and practical tips to make this transition from engineer to project manager smoother.

We have all seen best-in-class engineering project managers efficiently review a design, ask the designer a few questions for clarification, and then with mastery represent the design to achieve project goals with architects and contractors. How are they able to do this so effortlessly?

I believe an approach that focuses on three steps can be followed to achieve similar results. The first step is to keep top of mind the value that the design elements bring. The second step is to visualize the design in your head prior to reviewing the actual design. The third step is to focus on the significant elements or “big rocks” of the design while avoiding the temptation to get bogged down by low-impact details.

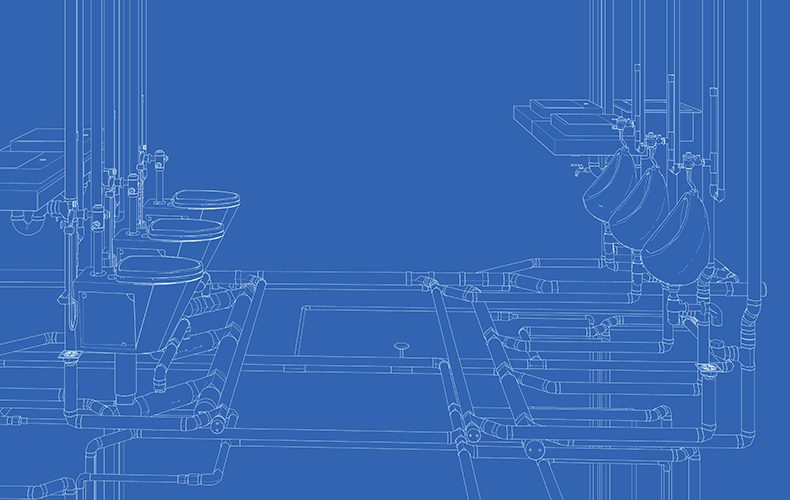

I will use a hospitality application domestic hot water distribution system example to demonstrate these points.

Step 1: Keep Top of Mind the Value that Design Elements Bring

Domestic hot water is an essential building service for sanitizing laundry and dishes, food preparation, general cleaning and personal hygiene including hand washing and showering. To maximize functionality and efficiency, the goal should be to safely deliver enough water at the temperature needed for the intended purpose with minimal wait time.

These systems are complex and require careful consideration. Hot water must be stored and distributed at high temperatures to prevent the growth of Legionella while simultaneously reduced to a temperature that diminishes the risk of scalding and thermal shock. Additionally, pressure must be boosted to reach remote fixtures and high floors, but then reduced to prevent harm to occupants and fixtures.

Hotel guests place high value on short wait times, high volume and the preferred pressure for showering. Insufficient hot water is a leading complaint of hotel guests, leading to reduced revenue. It is not uncommon for a hotel to take a room or entire banks of rooms (i.e., rooms serviced by a particular riser) out of service.

Domestic hot water systems are important systems for the health and safety of the occupants and the overall guest experience.

Step 2: Thoroughly Review Architectural Plans and Visualize the Design

A mechanical/electrical/plumbing design review should start with a thorough understanding of the architectural plans. As I review the architectural plans, I commit the building to memory while taking brief notes for quick reference on aspects applicable to the application.

For example, for a hotel, I would make note of the location of the kitchen and the laundry room. For a high-rise building, I would understand the function of each level such as parking, lobby, back of house and amenities. I would evaluate vertical stacking of fixtures and make note of where offsets in risers may need to occur.

At this point, I list key questions about what the design may look like. Is there a water softener? If so, does it serve all the water or the hot water only? Are there separate DHW loops to serve the laundry, the kitchen, public areas and guest rooms? How many floors on a high-rise make up each pressure zone? Is the hot water generation on a low floor serving up or on a high floor serving down?

My review of the plumbing drawings starts after I have a foundational understanding of the project, avoiding the confusion caused by trying to understand the plumbing design at the same time I am trying to understand the project. Furthermore, with my list of questions in hand, my review is focused on answering these questions and the parts of the design that deviate from my mental forecasting of it.

When reviewing a riser diagram, I am not trying to digest the whole diagram at once. Rather, I am sequentially answering my prepared questions, making note of a water softener, number of loops, number of floors per pressure zone, etc. The complex diagram suddenly feels much simpler and more understandable.

Step 3: Focus on the Big Rocks

of the Design

We all like the challenge of a good puzzle, but understanding MEP drawings should not be a puzzle. Clarity in the design documentation is a big rock and crucial to achieving reliable results. A DHW system requires many more components to properly operate than a typical hydronic system. And yet for some reason, in my experience, the documentation around these systems is often lacking.

I would expect to see the following elements clearly indicated on the plans or riser diagrams:

Location of thermostatic mixing valves, both master distribution and point of use.

Set point temperature leaving each thermostatic mixing valve and the return water setpoint for recirculation systems.

Flow rate required at each return branch.

Type of balancing device at each return branch and access method.

Schedule of balancing devices with tally of connected load.

Location of pressure-reducing valves and approximate set points.

Domestic hot water recirculation pump control mechanism (i.e., aquastat, pressure control, time clock, etc.).

A detail for PRVs, thermostatic mixing valves, recirculation pumps and balancing devices with devices required for proper startup.

To be clear, smaller systems often work fine, but for large stadiums, hospitals and hotels, lack of clarity in the documents can prove costly. Engineers’ specifications can leave ambiguity around design components affecting the system’s concept.

An example is a specification that allows either pressure-dependent, pressure-independent or temperature-actuated return balancing devices. This is not a decision that can be made in isolation from the pump performance and control method, and the testing, adjusting and balancing contractor’s scope.

Another example is the material specification. If the plans are sized for copper but the specification allows for PEX, the documents should clearly indicate that the pipe needs to be resized for the limitations of the material.

Focusing on big rocks means not focusing on other details. For example, I have never encountered a project where the design flowrate at each return branch was too low to maintain temperature, while I have been involved in several projects where the con-nected pump flowrate was not tallied, and the pump and return pipe was sized too small.

I have never been involved with a project where the master thermostatic mixing valve could not meet the peak demand, but I have been involved in several projects where the thermostatic mixing valve failed to properly operate during periods of low demand.

Domestic hot water distribution systems are more complex than they may appear and require careful attention to ensure proper design and construction. Project documents can be challenging to navigate, so it is essential to simplify the design to the core elements that can be easily referenced.

By focusing on the three key steps I mentioned, learning from recurring issues and minimizing effort on the details that rarely cause problems, engineers can transform into effective engineering pro-ject managers.

Justin Bowker, PE, has been part of the engineering team at TDIndustries since 2001. He became the manager of this team in 2009 and vice president of engineering in 2016. Under his leadership, the team challenges itself to harness technical approaches to provide fo-cused value to the owner on design/assist and design/build projects.